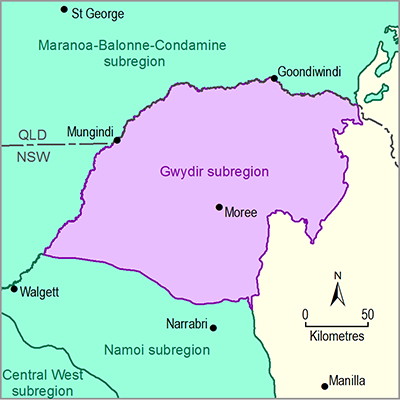

The Gwydir subregion is located within the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB) in northern NSW. To the north, it is separated from the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion by the Dumaresq, Macintyre and Barwon rivers and to the south from the Namoi subregion by the Namoi river basin topographic divide. These boundaries correspond to those for the Border Rivers and Gwydir river basins in NSW, but the eastern, upland part of the Border Rivers and Gwydir river basins is not included within this subregion. The eastern boundary of the Gwydir subregion is defined as the extent of the coal-bearing geology.

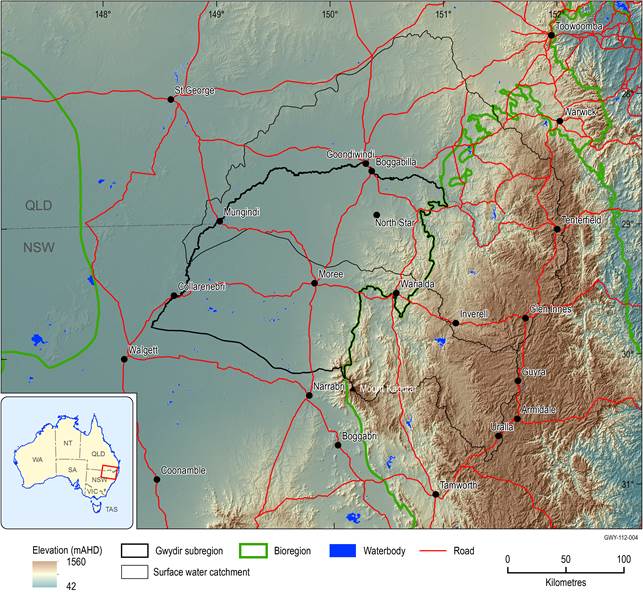

The Gwydir subregion spans an area of 28,109 km2, extending westward from the lower slopes of the New England Tablelands onto the low-lying riverine plains of the Barwon-Darling system. Maximum and minimum elevations for the subregion itself are 1300 mAHD near Mount Kaputar in the south and 110 mAHD near Collarenebri in the west, respectively (Figure 4).

The main rivers draining the subregion are the Gwydir and Macintyre-Barwon rivers. The Macintyre River rises in the region around Inverell (outside the subregion), flows in a north-westerly direction to Boggabilla before continuing west to meet the Barwon River near Mungindi. Sixteen kilometres upstream of Boggabilla the Dumaresq River flows into the Macintyre River, which then becomes the state border. The catchment area to the north of these rivers is part of Queensland and not included within the Gwydir subregion, but in the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion. The lower end of the Macintyre system is characterised by a complex of distributary streams and lagoon systems that flow away from the main channel when certain river levels are reached. These include Whalan, Callandoon and Dingo creeks, Boomi River and the Little Weir River. The confluence of the Macintyre and Weir rivers marks the start of the Barwon River. The headwaters of the Gwydir River (also outside the subregion) lie between Uralla and Guyra in the New England Tablelands. After descending the tablelands and slopes, the westerly flowing Gwydir River fans out into a number of anabranches and effluent channels, including Moomin Creek, Mehi River, Gingham Watercourse, Carole Creek and Gil Gil Creek, which wend their way to the Barwon River and its floodplains. More detail on the surface hydrology can be found in Section 1.1.5. The subregion’s most noteworthy water-dependent asset is the Ramsar-listed Gwydir Wetlands on the lower Gwydir and Gingham watercourses, and the Morella Watercourse, Boobera Lagoon and Pungbougal Lagoon on the Macintyre floodplains, which are listed in the Directory of Important Wetlands in Australia (Environment Australia, 2001) (Section 1.1.7).

Figure 4 Topography of the Gwydir subregion, generated from three second DEM

Source data: 3 second SRTM derived elevation model (DEM) version 1.0 (Geoscience Australia, 2011a)

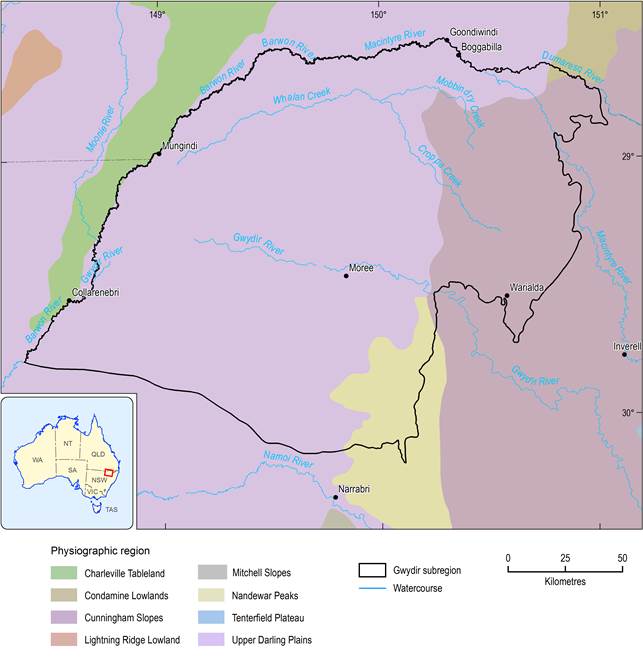

1.1.2.1.1 Physiographic regions

Physiographic regions are defined by a suite of landforms which have evolved in response to specific combination of climate and geologic controls (Jennings and Mabbutt, 1986). While the mapping criteria relate to landform attributes, the resultant mapped units can be described in terms of landform, underlying geology, regolith and soils (Pain et al., 2011).

The Gwydir subregion is dominated by the Upper Darling Plains physiographic region which is characterised by branching rivers incised into a regolith of predominantly alluvial sediments (>50%) with minimal saprolite (<20%) (Pain et al., 2011) (Figure 5). Saprolite refers to in situ weathered rock, whereas alluvial sediments indicate depositional environments, where the regolith comprises transported material, rather than material that has weathered in place. The eastern part of the subregion intersects the Cunningham Slopes and Nandewar Peaks physiographic regions. The more northern Cunningham Slopes are characterised by ridge and valley geomorphology in metamorphic rocks with regolith varying between highly weathered bedrock and soil on bedrock over most of the region. The small area of Nandewar Peaks in the south-east corner is a dissected volcanic pile landscape with a predominantly soil on bedrock regolith and other areas of moderately weathered bedrock.

The dominance of one physiographic region in the Gwydir subregion is reflected in the relative uniformity of soil type, land cover and land use.

Figure 5 Physiographic regions of the Gwydir subregion

As defined in Pain et al. (2011)

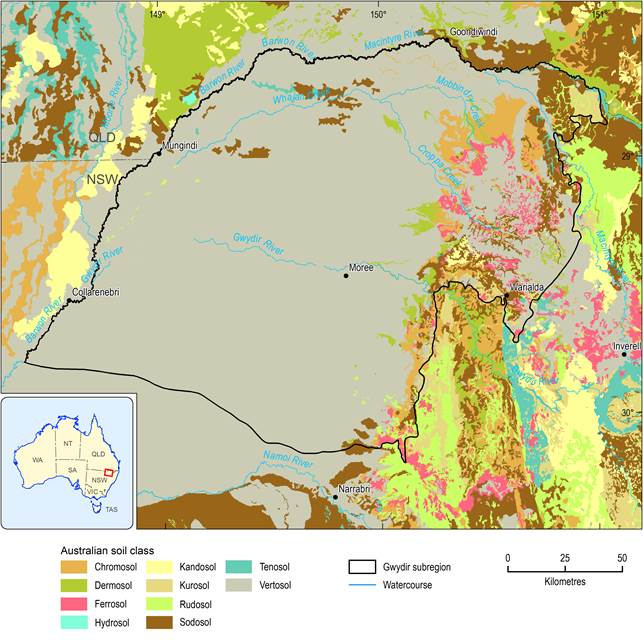

1.1.2.1.2 Soils and land capability

The Gwydir subregion has moderately fertile soils over most of its land surface, with a small strip of highly fertile soils along the Gwydir River valley around Moree and in some northern areas around Boggabilla (NSW OEH, 2012a). In the Australian Soil Classification system (Isbell, 2002), the soils of the Upper Darling Plains physiographic region are overwhelmingly Vertosols (Figure 6, Table 2), which are clay soils with shrink-swell properties that exhibit strong cracking when dry. From an agricultural perspective, they are well structured and have a good mix of pores for both transmitting and storing water, so plant growth on these soils is typically very good relative to other soil types. Vertosols are better suited to irrigated crops such as cotton, wheat, sorghum and rice than rain-fed crops because they can be worked under a very narrow range of moisture conditions. These self-mulching soils can withstand comparatively frequent cultivation without changes to structure.

Vertosols dominate in the Nandewar Peaks and Cunningham Slopes physiographic regions also, but other soils, such as Sodosols (soils having a high exchangeable sodium content), Ferrosols (soils having high free iron and generally high clay content) and Chromosols (soils showing strong texture contrast between surface and deeper soil layers) are significant in the eastern parts of the subregion (Figure 6). Localised areas of Dermosols (well-structured soils with high water holding capacity and high chemical fertility) can be found in the subregion also. The greater variability in soil types reflects the dominance of erosional and transportational surfaces on the slopes, in stark contrast to the depositional environments of the valleys and floodplains.

In the most recent systematic statewide assessment of NSW soil health, commenced in 2008 under the New South Wales Natural Resources Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Strategy 2010–2015 (NSW DECCW, 2010c), soil condition of the Gwydir subregion was assessed as generally good (i.e. small loss of condition relative to a reference condition for a range of soil indicators), with a likelihood of not changing in the future (NSW DECCW, 2010a). Soil condition is the ability of soil to deliver a range of essential services, including habitat for soil biota, nutrient cycling, water retention and primary production. The most limiting land and soil hazards in the subregion are soil structure and soil carbon decline, waterlogging and wind erosion (NSW EPA, 2012). Soil structure is the prime determinant of soil health, a decline in which means that soil permeability and water holding capacity are reduced (e.g. through compaction). Organic carbon is the main biological determinant of soil health and decline occurs when the removal of organic matter from the landscape exceeds its replacement. Wind erosion is a direct function of ground cover with bare soils, particularly Chromosols, more vulnerable to erosion than those where a good vegetation cover is maintained. Land management practices are the primary pressure on soil condition.

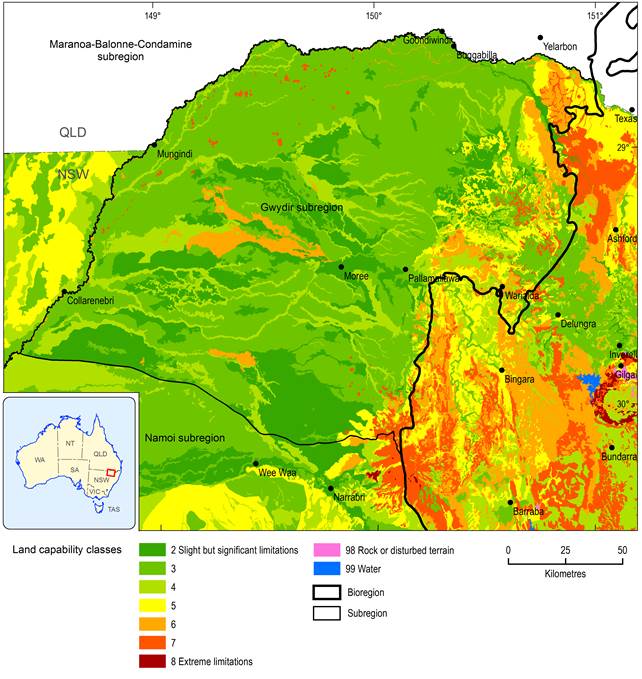

Land capability is the inherent physical capacity of the land to sustain long-term land uses and management practices without degradation to soil, land, air and water resources (Dent and Young, 1981). The land and soil capability classification scheme takes account of limitations for sustainable use arising from water erosion, wind erosion, salinity, topsoil acidification, shallow soils/rockiness, soil structure decline, waterlogging and mass movement (NSW OEH, 2012b). Figure 7 shows land and soil capability classification for the Gwydir subregion based on the most limiting hazard. Class 1 represents land capable of supporting most land uses with minimal conservation management, while Class 8 land has many limitations to use and is best left for conservation. For the most part, lands in the subregion are land and soil capability Classes 2 and 3, meaning they can support high impact land uses through easily implemented more intensive management practices. Along streamlines, the land is typically land and soil capability Class 4 and not capable of supporting high impact uses without very specialised management. The Gwydir Wetlands, an area just south of the Mehi River and the eastern margins of the subregion are Class 6 lands and there are localised patches of Class 7 land in the Warrumbungle Ranges and east and north of Warialda, where shallow soils and vulnerability to water erosion and mass movement seriously limit land use options. These areas are best suited to light grazing, forestry and nature conservation (NSW OEH, 2012b).

Figure 6 Soils classified using the Australian Soil Classification

Source data: National Soil Grids (ASRIS, 2011)

Table 2 Soils, classified using Australian Soil Classification (Isbell, 2002)

|

ASC soil class |

Percentage of total area of subregion (%) |

|---|---|

|

Vertosols |

84% |

|

Sodosols |

6% |

|

Chromosols |

4% |

|

Dermosols |

2% |

|

Ferrosols |

2% |

|

Kurosols |

1% |

|

Rudosols |

1% |

In 2009, the former Border Rivers-Gwydir Catchment Management Authority (Border Rivers-Gwydir CMA) and the former NSW Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water (NSW DECCW) assessed the extent to which land was being used within capability in the NSW Border Rivers and Gwydir river basins. In the Gwydir subregion, the majority of land is being used ‘at capability’, meaning that the risk of degradation under current land uses and management is low (NSW DECCW, 2010a).

Figure 7 Land and soil capability

Source data: Land and Soil Capability mapping of NSW (NSW OEH, 2013a)

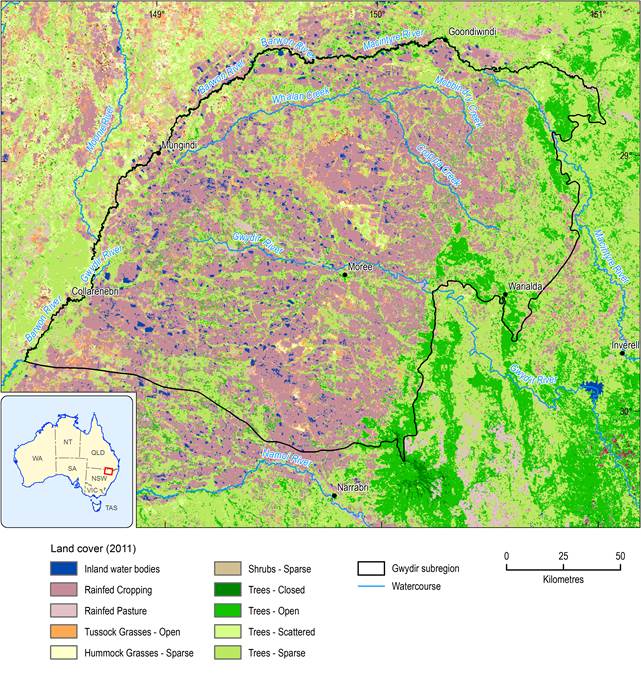

1.1.2.1.3 Land cover

Figure 8 shows the land cover for the subregion in 2008, based on remotely sensed Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on the Terra and Aqua satellites that have been post-processed to convert vegetation greenness to a land cover type (Geoscience Australia, 2011b). Pasture and crops are the dominant land covers (54%), with open, scattered and sparse tree covers accounting for 38% of the land cover. Tussock grasses and a small proportion of hummock grasses cover 5% of the land area (Table 3).

The landscape in the subregion has been heavily modified. The majority of the land is classified as ‘non-native or other’ which means predominantly crops and non-native pastures, with a very small fraction of urban, industrial and infrastructure land cover types. The subregion boasts very little intact native vegetation cover and less than 0.4% of land is managed for conservation. The 2010 State of the Catchment report for the Border Rivers-Gwydir region (NSW DECCW, 2010d) rated the vegetation condition as fair and the pressures on land cover as moderate. However, the subregion has a higher proportion of transformed land cover than the upland areas of the wider Border Rivers and Gwydir river basins, and therefore vegetation condition could well be poor.

Source data: The National Dynamic Land Cover Dataset, Geoscience Australia (2011b)

The methods used to produce the land cover map are not very sensitive to use of irrigation water and irrigated land covers are often mapped as rain-fed covers. For irrigated land covers, the land use map (Figure 9) should be consulted.

Of the remnant communities, the floodplain woodlands of coolibah are the most extensive, with occasional myall woodlands and whitewood and belah woodlands with lignum and mimosa. The plains once supported extensive areas of Mitchell and plains grass communities, but these are now much reduced in the area. They can still be found on the plains south-west of Moree. Other communities occurring on the higher parts of the floodplain include poplar box woodlands, wilga, brigalow, white cypress and silver leaf ironbark (Border Rivers-Gwydir CMA, 2007).

A number of ecological communities, which may once have or still do occur within the subregion are protected under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 and the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Table 4). The marsh club-rush sedgeland at the core of the lower Gwydir Wetlands and found only in the Gwydir valley was listed as an endangered ecological community by NSW in 2010. The riverine plains of the Gwydir and Mehi rivers also support remnant areas of carbeen open forest, myall woodland, and inland grey box woodland (Green et al., 2011, 2012). The Border Rivers-Gwydir Catchment Action Plan 2013 to 2023 has set targets for the Western Plains and Brigalow Country areas to increase native vegetation cover by 2% by 2023 (Border Rivers-Gwydir CMA, 2013).

Seasonal and semi-permanent wetlands occur along the Gingham and Gwydir watercourses. About 40,000 ha of wetlands in the river basin are recognised as being internationally or nationally important.

Table 3 Areas and percentage of subregion for each land cover type in Gwydir subregion

Table 4 Ecological communities in the Gwydir subregion that are listed as threatened under the the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 and the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

Source data: NSW DEH (2013a) and Department of the Environment (2013a)

See also section 1.1.7 Ecology