- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

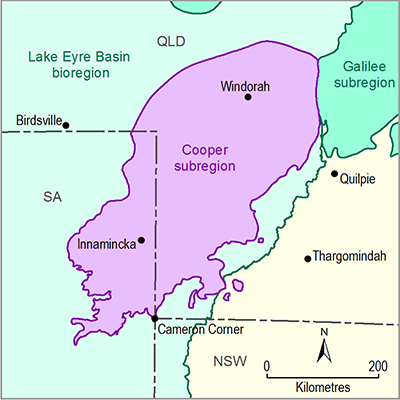

- Cooper subregion

- 1.1 Context statement for the Cooper subregion

- 1.1.7 Ecology

- 1.1.7.2 Terrestrial species and communities

1.1.7.2.1 Principal vegetation types and distribution patterns

According to the NVIS v4.1 data (Australian Government Department of the Environment, Dataset 3), saltbush and/or bluebush shrublands is the most widespread terrestrial NVIS v4.1 major vegetation subgroup in the Cooper subregion (22.3% by area, occurring primarily in the western half of the subregion), followed by Mitchell grass (Astrebla) tussock grasslands (15.4%, primarily in the central and northern parts of the subregion), Hummock grasslands (11.3%) and Mulga (Acacia aneura) open woodlands and sparse shrublands (10.6%). Eleven other vegetation subgroups each cover 1 to 10% of the subregion (130,000 to 1,300,000 ha each) and 19 vegetation subgroups (excluding ‘No data’) each cover less than 1% of the subregion (<130,000 ha each) (Table 10).

At smaller-scale mapping, these vegetation subgroups have been delineated as discrete communities that respond to drainage patterns, topographic and edaphic variation. However, in larger-scale mapping, vegetation type mosaics have been identified, causing more homogeneous interpretation of the NVIS classification and thus causing difficulty in harmonising the vegetation mapping across state borders (Figure 34). The consequence of this scale issue is that major boundaries between vegetation subgroups occur along state borders, when there are no corresponding boundaries in terms of surface geology, soils or drainage patterns. For example, east of Moomba, saltbush and/or bluebush shrublands in SA (the most common NVIS vegetation subgroup in the subregion) abut Hummock grasslands in Queensland (the third most common NVIS in the subregion). Furthermore, a complex of vegetation subgroups along Cooper Creek and its floodplains in Queensland are not mapped across the border into SA. Due to this difference in the scale of mapping across state borders it not possible to develop relative abundance of NVIS major vegetation subgroups as terrestrial ecological context for the Cooper subregion as a whole.

1.1.7.2.2 Recent change and trend

Very early in the Euro-Australian settlement of central and western Queensland, the Eucalyptus open woodlands with a grassy understorey (along Cooper Creek and major tributaries), the Mitchell grass (Astrebla) tussock grasslands (on cracking clay soils) and all other tussock grasslands and wetlands were recognised as vegetation types with a combination of plant growth and palatability characteristics that would yield high livestock productivity under pastoral grazing systems (Orr and Holmes, 1984; Burrows et al., 1988). After more than a century of extensive cattle grazing, the bulk of these vegetation types in the Cooper subregion are now classed as ‘modified’ or ‘transformed’, according to the Vegetation Assets, States and Transitions (VAST) classification of Thackway and Lesslie (2005). In this classification, ‘modified’ and ‘transformed’ mean that the dominant structuring native species are present, but their levels of dominance have been significantly altered, and their natural regenerative capacity is limited or at risk under past and/or current land use or land management practice. Adventive, exotic plant species may be present or common, but are only co-dominant in the understorey where the vegetation is ‘transformed’. Remote and unpalatable vegetation types, such as Hummock grasslands (on desert dune fields), are the only vegetation types in the Cooper subregion that retain their original or ‘residual’ status according to the VAST classification.

As part of Queensland activities for the Australian Collaborative Rangeland Information System (ACRIS), Bastin et al. (2014) have recently completed an analysis of trend in condition of the non-woody component of the native terrestrial vegetation across Queensland’s rangelands, including the north-eastern part of the Cooper subregion. Using multi-temporal remote sensing data and analyses based on landscape heterogeneity and functionality, Bastin et al. report that the three IBRA subregions that partly lie within the Cooper subregion showed approximately stable to slightly improving range condition over the period 1988 to either 2003 or 2005 (depending on drought sequences).

1.1.7.2.3 Species and ecological communities of national significance

Table 12 lists species of national significance listed under the Commonwealth’s Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act) that are known to occur in the Cooper subregion through specimens or human observations, or for which their occurrence is likely based upon analysis of the distribution of suitable habitat. All but one of those species can be identified as having low or no water dependence in the sense of the BA methodology (Barrett et al., 2013) and thus can be considered terrestrial.

There are no EPBC-listed terrestrial ecological communities within, or near, the Cooper subregion.

1.1.7.2.4 Species of regional significance

Table 13 lists taxa of regional significance under Queensland’s Nature Conservation Act 1992. There are 45 taxa that occur in the Cooper subregion but are not also listed nationally.

Table 14 lists the 48 taxa of regional significance under NSW’s Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995.

Table 15 lists the taxa (including some subspecies) of regional significance under SA’s National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. There are 82 taxa that occur in the Cooper subregion but are not also listed nationally. Fifty-three of those species can be identified as having low or no water dependence in the sense of the BA methodology (Barrett et al., 2013) and thus can be considered terrestrial.

Table 12 Species and ecological communities in the Cooper subregion that are listed as threatened nationally under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

Data: Department of the Environment (2014d)

Source database includes comments on water dependence

Table 13 Species in the Queensland part of the Cooper subregion (Shires of Barcoo, Bulloo and Quilpie, and parts of Shires of Diamantina and Longreach) that are listed as threatened under Queensland‘s Nature Conservation Act 1992 and Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 2006 (updated to 27 September 2013), and under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

Data: DSITIA (Dataset 16, Dataset 17)

Source database does not include comments on water dependence, but a preliminary comment on water dependence is included here for consistency with Table 12.

Table 14 Species in the NSW part of the Cooper subregion (Strzelecki Desert subregion of the West Dunefields Catchment Management Authority) that are listed as threatened under NSW’s Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995

Data: NSW Office of Environment and Heritage (Dataset 18). Source database does not include comments on water dependence, but a preliminary comment on water dependence is included here for consistency with Table 12.

Table 15 Species in the South Australian part of the Cooper subregion (Coongie, Sturt Stony Desert, Lake Pure and Strzelecki Desert IBRA subregions) that are listed as threatened under SA’s National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972, including their threat status in the South Australian Outback region as assessed by Gillam and Urban (2013)

Data: Gillam and Urban (2013). Source database does not include comments on water dependence, but a preliminary comment on water dependence is included here for consistency with Table 12.

‘-‘ means insufficient data