- Home

- Impact assessment for the Beetaloo GBA region (stage 3)

- 4 Assessment results

- 4.3 Potential impacts on the environment

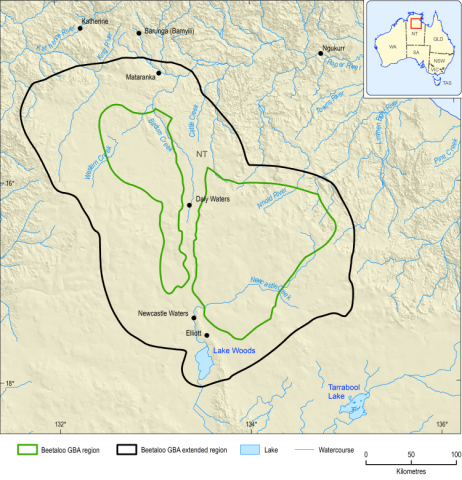

For this assessment, the environment of the Beetaloo GBA region, excluding aquatic environments, has been considered in terms of 3 ecosystems based on (i) terrestrial vegetation that is dominated by rainfall dependent open woodlands, (ii) riparian ecosystems that include flora and fauna that are dependent on the presence of rivers and streams and (iii) ephemeral wetlands. Terrestrial vegetation accounts for around 90% of the region.

Potential impacts on terrestrial vegetation

Rain-fed open woodlands dominate the Beetaloo GBA region. Activities at the surface such as civil construction, seismic acquisition, transport of materials and equipment and decommissioning and rehabilitation ( Figure 13 ) may cause changes in terrestrial vegetation extent and condition . Pathways that are of ‘potential concern’ and warrant more detailed local-scale assessment are related to invasive plants and insects , vegetation removal and vehicle movement . Existing management controls can avoid and mitigate these potential impacts.

Potential impacts on areas of rainfall-dependent vegetation in the Beetaloo GBA region are explored through the terrestrial vegetation extent and condition endpoint. Terrestrial vegetation encompasses the largest portion of the Beetaloo GBA extended region and provides habitat for a wide range of species, including 4 of the threatened fauna species assessed: greater bilby ( Macrotis lagotis), crested shrike-tit (northern) ( Falcunculus (frontatus) whitei), Gouldian finch ( Erythrura gouldiae) and grey falcon ( Falco hypoleucos). The area is predominantly open woodlands over a grassy understorey, although it does include several landscape classes and a range of vegetation communities (see Figure 12 for an example of typical terrestrial vegetation).

FIGURE 12 Bullwaddy vegetation, near the Bullwaddy Conservation Reserve in the Beetaloo GBA region, one of the vegetation types within the terrestrial vegetation endpoint

Source: Geological and Bioregional Assessment Program, Chris Pavey (CSIRO)

Element: GBA-BEE-3-540

Impacts from activities such as civil construction , seismic acquisition , transport of materials and equipment and decommissioning and rehabilitation are unavoidable in resource development ( Figure 13 ). However, impacts can be avoided, minimised or mitigated through adherence to strategies outlined in the Land clearing guidelines for the Northern Territory (Northern Territory Government, 2020) and the Code (Northern Territory Government, 2019c). Mitigation strategies include locating infrastructure away from potentially sensitive habitats to avoid vegetation removal in their their vicinity, control of invasive species (weeds and carnivores) and minimisation of vehicle access to previously undisturbed areas.

Potential impacts on wetlands and riparian vegetation

The Beetaloo GBA extended region has small areas of wetlands (3%) and riparian vegetation (2%) that have high ecological value and provide habitat for many species. Key potential impacts for wetland condition and riparian vegetation extent and condition are from civil construction (for example, roads, well pads or laydown yards) and any activity that requires vehicle movement beyond designated roads, such as seismic acquisition.

The wetland condition endpoint covers a relatively small area, representing just 3% of the Beetaloo GBA extended region. It includes ephemeral lakes, swamps and channel environments that are inundated less than 70% of the time, including the Directory of important wetlands-listed Lake Woods. Lake Woods is the largest receiving lake in the Beetaloo GBA extended region (Environment Australia, 2001) and a significant open water environment and lignum swamp that supports breeding sites for 23 species of waterbird. Wetlands and the vegetation they support, provide important habitats for the Australian painted snipe ( Rostratula australis).

The riparian vegetation extent and condition endpoint includes vegetation associated with areas mapped as watercourses and all terrestrial groundwater-dependent ecosystems, whose occurrence is mostly confined to the north of the Beetaloo GBA region and makes up around 2% of the land area in the Beetaloo GBA extended region. Riparian areas adjacent to watercourses typically have higher species richness than the surrounding landscape and vegetation is often denser due to greater water availability (Woinarski et al., 2000). Riparian areas are known to support species such as the Gouldian finch, which needs to drink daily during breeding (Dostine et al., 2001; O’Malley, 2006), and the grey falcon, which can use tall trees including river red gums along watercourses as nesting sites (Marchant and Higgins, 1993).

Pathways of ‘potential concern’ for wetland condition and riparian vegetation extent and ondition are the same as those for terrestrial vegetation extent and condition , primarily involving disturbance at the surface ( Figure 13 ). The Land clearing guidelines for the Northern Territory (Northern Territory Government, 2020) and the Code (Northern Territory Government, 2019c) require that activities in these vegetation communities be minimised or avoided. Therefore the pathways for impact for these endpoints are indirect.

Potential impacts related to accidental spills

Accidental release of chemicals is of ‘potential concern for wetland condition and riparian vegetation extent and condition through surface water contamination. However, there is high confidence that existing regulations and mitigation strategies related to accidental release can mitigate potential impacts on wetlands and riparian vegetation.

As surface water is a component of both wetlands and riparian vegetation, there is potential for surface water contamination to affect their condition. Spills onto the land surface outside of bunded areas ( accidental release ) is of ‘potential concern’ for wetlands and riparian vegetation through surface water contamination . Accidental release may result from any activity that involves the transport, handling, storage and use of chemicals. Australian and international literature indicates that spills are infrequent, although rates are highly variable (dependingon local conditions and practices) and difficult to define (Huddlestone-Holmes et al., 2017). The spatial extent of spills beyond containment is likely to be limited to a scale of tens of square metres over a short duration. Infrequent chemical discharge to the environment through accidental release may briefly exceed guideline values and harm aquatic species and other biota. However, there is high confidence that existing regulations and mitigation strategies related to accidental release can mitigate potential impacts on wetlands and riparian vegetation.